Last week, a writer told me an agent story that is the stuff authors’ nightmares are made of. The details of this story are always similar: after toiling away on their novel for years, a hopeful author summons all of their courage to send their work into the world. They send off query letters and wait. Then something incredible happens: an agent falls in love with their work. And it’s a match! Hurray! Then for whatever reason, the agent ghosts. Perhaps they reappear with some vague information and apologies about their absence, but ultimately, the result is that the author’s work is never properly submitted. This process can take months or years to unfold while the author waits it out as this writer had: too polite to draw the line with the flakey agent, too scared to risk the chance they’ve been given. They’ve done their research, they know how hard it is to get an agent: what if they can’t get another? Maybe flakey agent will come around.

“I tried really hard not to bug her too much,” the writer told me, as she recounted the tale of not one but two flakey agents that had put her through the ringer.

None of what happened was this writer’s fault, but she’d accidently become a doormat after getting caught in a diabolical trap so many of us find ourselves in, that of trying to be the “Cool Author”.

There is a brilliant passage in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl that had women round the world nodding their heads. It concerns that mythical being of post-feminist pop culture: The Cool Girl.

“Men always say that as the defining compliment, don’t they? She’s a cool girl. Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl.”

This resonated hard with so many of us, whether we’ve played the Cool Girl or not in previous relationships, we know the trope all too well. We’ve surely hit up against the expectation of it, and her equally legendary counterpart: the Crazy Girl (alternately known simply as That Girl i.e. “I don’t want to be that girl.”). It’s a false dichotomy: be Cool lest everyone think you’re Crazy.

The Crazy Girl in her extreme incarnation is the stalker, the nut job, the stage five clinger, the jealous, vindictive, obsessive nightmare woman. Of course this woman, though rare, is out there, though usually far less actually dangerous than her male counterpart. Some people are crazy, some of them are women, sure. But the Crazy Girl is more often used as a shaming tool to ensure that women don’t express their needs and wants in a way that will make a man uncomfortable, or to, heaven forbid, call him on his bad or childish behavior. Still, we all fear this label.

I’ve noticed that many writers, male and female, similarly fear being the Crazy Author. Now, just as some Crazy Girls exist, so does the Crazy Author. I have met a handful that truly earned the label in my many years working in publishing, and the thing about the Crazy Author is—much like the Crazy Girl—they are neither aware that they are being the Crazy, nor are they terribly concerned about being the Crazy, they’re just running with it. They berate you for not doing things exactly as they wanted, they yell and cry and throw temper tantrums and tell their agent to call your boss. They call you on weekends, there is no spot on NPR or rave review that will satiate them. They are impossible to please, ego-driven, nightmare humans. Everyone in publishing has a couple of stories. No one wants to be the Crazy Author, because the Crazy author is the worst.

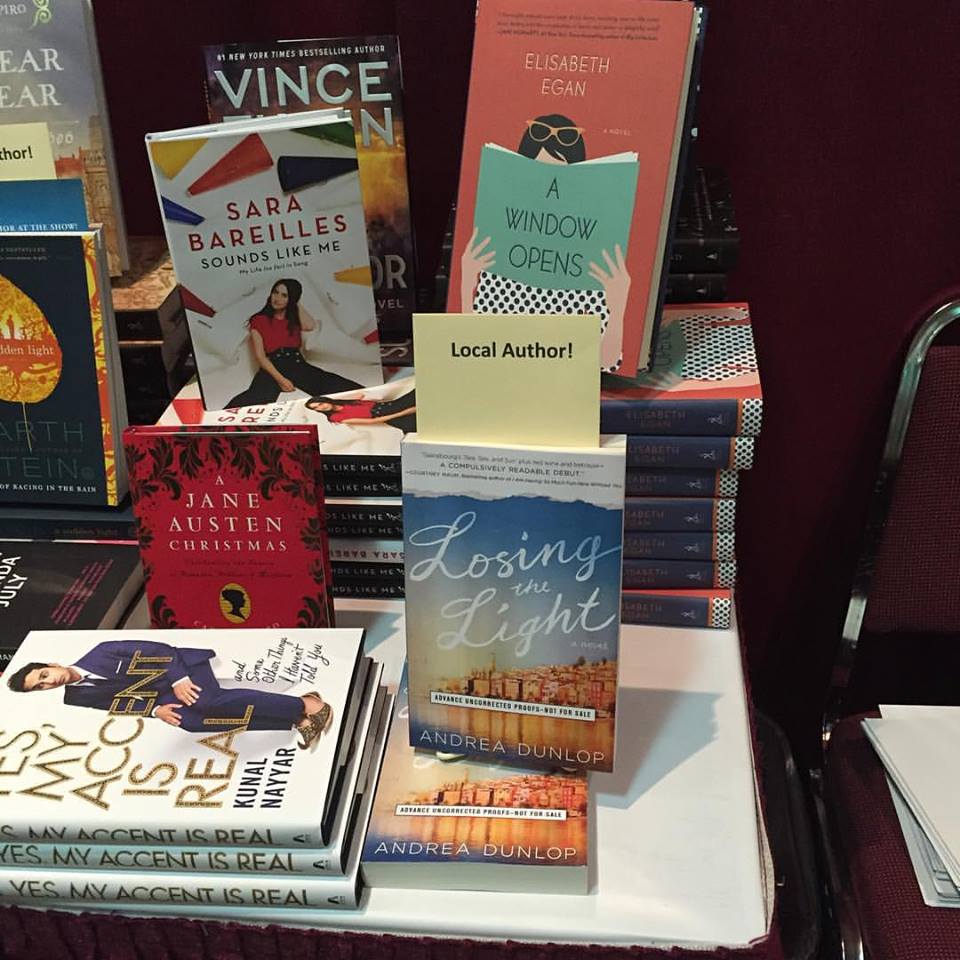

Much better to be the Cool Author, the one everyone goes the extra mile for and thinks “books like this are the reason I work in publishing”, the author who sends flowers to the assistants, and treats to the staff, and that everyone in the office gets excited about when they stop by.

This is a fine aspiration. But, just as in romantic relationships, when the desire to be Cool instead of Crazy, clouds our judgement to the point that we endure bad treatment or don’t speak our mind, (“Whatever you guys want! I don’t mind! It’s only my treasured novel that I spent ten years on, but I’m easy! I’m cool!”) it becomes a problem.

My advice? Be good to the people who work on your book. Most of the agents and other publishing folks I know (and I know many) are some of the kindest, hardest working, brightest, most passionate people I’ve ever met. It’s why I stay in this industry despite its foibles. But if you do get a bad apple, don’t stand for it. You have a right to be treated fairly and respectfully; you have a right to expect trust and good communication from those you work with. Whatever you do, don’t trade your dignity for Cool.