I suppose many people suffer from feeling like frauds, but writers seem to have a particular yen for it. I have yet to meet an accountant or lawyer who questions whether they are a real accountant or lawyer; they may wonder whether they’re a good accountant or lawyer but not whether they are a real one.

For all that opinions abound on the subject of what differentiates a “real” writer from their somehow less authentic counterparts, there is no agreement, no test one can pass or certification one can get that will settle the subject.

Is a real writer someone who is published? If so, then how big must their publisher be for it to count? Or does being published by a small indie press make them more authentic? What about self-published authors?

Is a real writer someone who has their MFA? Someone who has won prizes? Someone who is read by lots of people, or does it only need to be the right people? Do, in fact, only certain kinds of readers even count?

Perhaps the reason so many writers question their “realness” in the trade is exactly because there is no piece of outside validation to tell them when they’re real. Many a writer with accolades that would seemingly assure them of their realness—publication, awards, teaching gigs—have confessed to me that they fear they are not, in fact, the real thing.

Many of us have some perfect ideal of what a real writer is: maybe it’s Dorothy Parker at the Algonquin round table, maybe it’s a tortured soul like David Foster Wallace. Recently a conference participant lamented to me that she wished that she could have lived in the time of Hemingway, he didn’t have to market himself like authors do now. I reminded her that Hemingway was a miserable alcoholic who killed himself, so maybe having to learn to use Twitter wasn’t actually the worst fate that could befall a person.

I hate it when people get overly precious about writing—when they claim they must do it or they would perish, and that if you cannot claim the same, you’re not “real”. I, for one, can think of several situations in which I wouldn’t need to write: if I found myself having to flee a war-torn country, perhaps, or if I were preoccupied with finding food for my family. The writing life is a privileged one, let’s not pretend otherwise. That said, there’s something to that intense devotion. If anything, that may be where the realness lies.

The moment I felt like the real thing was my lowest as a writer. I’d just gone out with my first novel and it had been rejected all around town. My agent told me we’d reached the end of the road. That call I’d been anxiously waiting for—the one that was going to make me real—wasn’t coming. I was still young enough then for this to feel like the worst thing that had ever happened to me. I was bereft. But I didn’t want to give up then, and so I knew that I wouldn’t ever. And, much as you know you really love someone only after that love has been tested, it was then that I began to feel real.

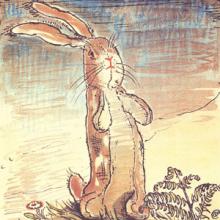

Here I’ll defer to the eternal wisdom of The Velveteen Rabbit’s skin horse on being real: "You become. It takes a long time. That's why it doesn't happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept."

It might not be a pretty process, becoming real, but it lasts for always.